Words by Mia McKenzie

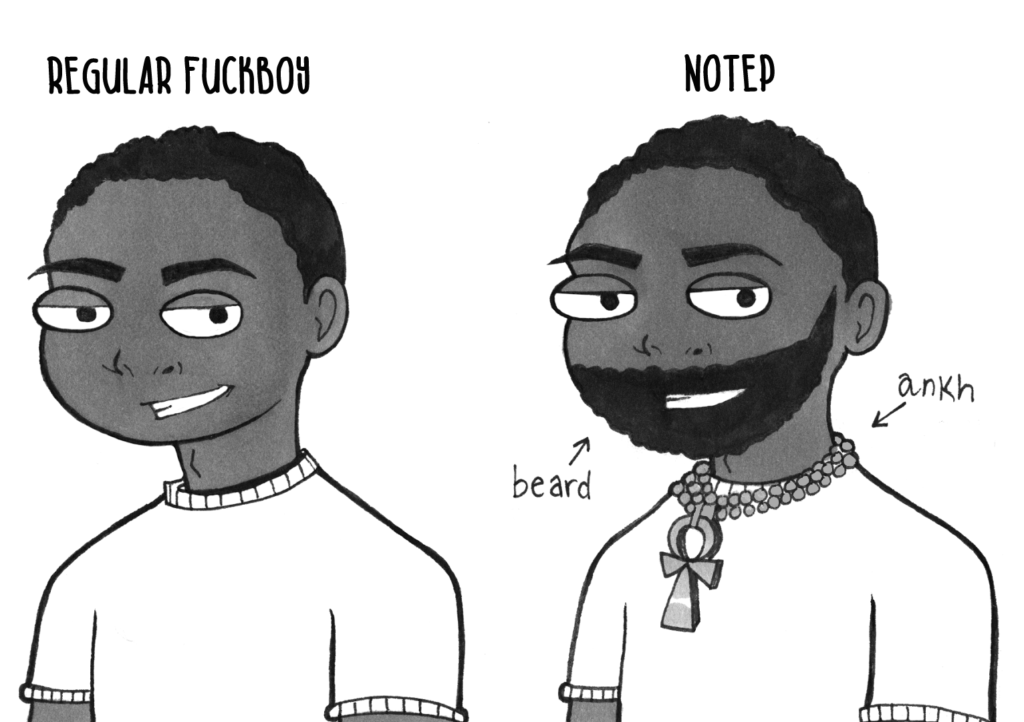

Drawings by Ritapa Neogi

I’ve always wanted kids and, since I started identifying as a feminist at around twenty years old, I’ve wanted those kids to be daughters. The idea of raising little Black girls, of loving them and giving them everything they’d need to become free and happy Black women, made me really excited about the possibilities of motherhood. I imagined instilling in my little girls radical Black feminist teachings that would help them navigate an anti-Black, anti-woman, anti-Black woman world, including:

- Fuck you, pay me

- The art of breaking white people’s fingers when they touch you without permission (and how to make it look like an accident) and

- How to tell the difference between a notep and just a regular fuckboy

I don’t remember when wanting daughters turned into being absolutely sure I’d have daughters, but somewhere along the way I kind of forgot that there was even a chance that my future children wouldn’t be girls. I rationalized that my own mother only had daughters and that her mother mostly had daughters, too. Having daughters was in my genes. Obvi. When I met my wife and we eventually talked about starting a family together, she also expressed a desire to have daughters. Daughters were, in my mind, a sure thing. But…it didn’t actually work out that way.

The way it worked out is that we now have a son. As far as we know. We have a baby with a penis, who is most likely to turn out to be a cisgender boy, statistically-speaking. And that cisgender boy is most likely to grow up to be a cisgender man. Which, not gonna lie, lowkey freaks me out. I mean, I love him. Like, a crazy amount. More than seems sustainable sometimes. (How many hours can I spend staring at him to make sure he’s still breathing before it’s too much????) But loving him doesn’t erase the fact that, for me, having a boy child is kind of a weird experience.

“But, Mia,” you might be thinking, “gender is a social construct!” To which I say: OKAY BUT IT’S STILL WEIRD, THOUGH. Because:

1. We don’t have very much experience with baby penises. (Or adult ones, tbh.)

Our first foray into the topic of baby penises was when we had to decide if we were going to circumcise our son. Note: whether to cut off a piece of your kid’s junk or not is a weird thing to even have to make a decision about.

We decided against the cutting of the baby junk, but then we were super confused about how to wash his lil uncircumcised penis. Like, were we supposed to push back the foreskin and clean up under there? If so, with what? Like, a Q-tip?? Because that sounds really difficult! He’s a super squirmy baby and his penis is really small compared to our giant adult-hands. What if we break it????? NO ONE WANTS TO BE THE PARENT WHO BROKE THEIR KID’S DICK.

Luckily, a friend told us that baby penis foreskin is fused and unretractable, which is a relief. For now. But at some point we’re going to have to clean up under there and, eventually, teach him how to clean up under there, too, because no one wants to be the parent of the kid with the stinky dick, either.

2. Gender seeps in, even when we try to keep it out.

When we found out we were most likely going to have a cisgender boy, we decided not to tell anyone. We didn’t want people to start acting all gendery about our kid before he was even born. We told our family and friends that we were open to all colors of baby gear. We imagined people would buy pink and blue and everything in between. But guess what? No one bought anything pink. Pink is apparently so much for girls that no one wanted to risk getting something pink for a baby who might turn out to be a boy. Not even our queer family and friends. A girl in blue is fine, I guess, but a boy in pink had people like: DIS TEW MUCH.

It wasn’t just our family and friends who had a hard time, though. As hard as we both tried, once the baby was born, my wife and I couldn’t help falling into weird gender stuff, either. Where once we’d cringed whenever a nurse who knew we were having a boy called him a “little man” we both started doing it ourselves once he was here. I’d catch myself saying “little man” and the urge to punch myself in the face was almost overwhelming. No one calls baby girls “little women”. BECAUSE IT’S WEIRD. Still, we had to make a conscious effort to stop saying “little man” and we’ve mostly succeeded. My wife still calls him “buddy” a whole lot, though.

3. We probably won’t have a shared experience of gender with our kid

When we found out that the embryo we were transferring was “male” (by science-y standards), we grappled with both what it means to not have the girl we always wanted and what we even mean when we say we wanted a girl. As people who try not to think rigidly about gender, what does wanting a girl—and not wanting a boy—really mean? What is it that we actually wanted?

We agreed that couldn’t really be it. Because, like, what if the kid had a vagina but later turned out to be a trans boy and not, in fact, a girl? We know having a vagina doesn’t make you a girl, so what was it we actually wanted? Neither of us were sure, but that didn’t stop us from wanting it, whatever it was.

What I’ve figured out since then is that when we said we wanted a girl what we really meant was that we wanted a child with whom we shared an experience of gender. This is, ultimately, why probably having a cis boy child feels weird. As someone who identifies as, and is perceived as, a woman—as a Black woman, especially—I’ve had particular kinds of experiences of fuckery in the world, such as:

- Men and white women thinking they’re smarter than me, when they almost never are

- Hardly being able to walk down the street without being forced into an unwanted interaction with some man. Often some ugly man. Way too often some ugly man with gold teeth. And

- White people assuming I’m the help, no matter what I’m wearing. (No, I don’t work at this Target, Miss White Lady, how did the evening gown not give it away?)

Jokes aside, though, Black womanhood is real as fuck, folks. Social constructs or not. It’s from other Black women that I learned how to navigate the world, how to thrive in it. Loving my son from the moment I found out I was pregnant didn’t stop me mourning the daughter I’d probably never give birth to, the relationship with her I’d never have, the things I’d never be able to pass on to her as a Black woman raising a Black girl. I still mourn that and it’s possible I always will.

But what I’ve learned from the experience of having a son when I wanted a daughter is that we don’t actually have any control over any of this at all (even with advanced technology), as much as it might comfort us to think we do. The daughter I always wanted could have turned out to be a boy or to have identified as neither of those genders. The son I have might ask us to call him “she” or “they” one day. In the reality that exists outside of my head, outside of my desires, whatever I “always wanted” is, as it turns out, entirely irrelevant.

I’m happy with my baby boy. My little love. My Story. I’m grateful he chose me to come through into the world. Because, regardless of whatever I always wanted, he’s very much the baby I want.

Want to bring Mia to talk race, queerness and feminism at your school or community event? She’s now booking for Fall 2017!

Want to bring Mia to talk race, queerness and feminism at your school or community event? She’s now booking for Fall 2017!